Introduction

Human decision-making is often the result of extended chains of thought [1, 2]. Recent work has shown that explicit intermediate reasoning (“rationales”) can improve large language model (LLM) performance as well [3–8]. For example, [5] demonstrated that LLMs explicitly trained to use

“scratchpads” for intermediate steps can attain perfect in-distribution performance on arithmetic,and strong out-of-distribution generalization, while models trained to predict answers directly fail to do either. These works suggest that generating explicit rationales before giving a final answer (“rationale generation”) is valuable for LLMs across diverse tasks including mathematical reasoning, commonsense reasoning, code evaluation, social bias inference, and natural language inference. However, the two primary methods for inducing rationale generation both have serious drawbacks.

人类决策常常是经过长时间思考的结果[1,2]。最近的研究表明,显式中间推理(“原因”)也可以提高大型语言模型(LLM)的性能[3-8]。例如,[5]证明了LLMs在使用“草稿本”进行中间步骤训练时可以达到算术完美分布内性能和强大的分布外泛化,而直接预测答案的模型则无法做到这一点。这些工作表明,在给出最终答案之前生成显式原因(“原因生成”)对于包括数学推理、常识推理、代码评估、社会偏见推断和自然语言推断在内的各种任务都有价值。然而,引导原因生成的两种主要方法都存在严重缺陷。

One approach to rationale generation is the construction of a fine-tuning dataset of rationales, either manually by human annotators or automatically with hand-crafted templates [3–5, 9]. Manual methods are expensive, and it is infeasible to construct such a dataset for each interesting problem [3]. Meanwhile, template-based methods rely on automatically-generated rationales but only work when a general solution is already known [5] or reasonable hard-coded heuristics can be made [4].

一种生成理由的方法是构建一个微调数据集,可以通过人工注释员手动创建或使用手工制作的模板进行自动化[3-5,9]。手动方法成本昂贵,并且对于每个想了解的问题都无法构建这样的数据集[3]。同时,基于模板的推理生成器,仅在已知通用解决方案时才有效[5]或者可以制定合理硬编码启发式算法时才有效[4]。

An alternative is to leverage in-context learning by including only a few rationale examples in the language model prompt. This has been shown to improve accuracy on mathematical and symbolic reasoning tasks relative to prompting without rationales (“direct” prompting) [5, 6]. Yet, while few-shot techniques with rationales tend to outperform their non-reasoning counterparts, they generally substantially underperform models fine-tuned to directly predict answers using larger datasets [5, 6].

一种替代方法是通过在语言模型提示中仅包含少量的推理示例来利用上下文学习。研究表明,相对于没有推理(“直接”提示)的提示方式,这可以提高数学和符号推理任务的准确性[5,6]。然而,虽然带有推理的小样本技术往往优于它们不涉及推理的对应物,但它们通常远不如使用更大数据集进行直接预测答案的微调模型[5,6]。

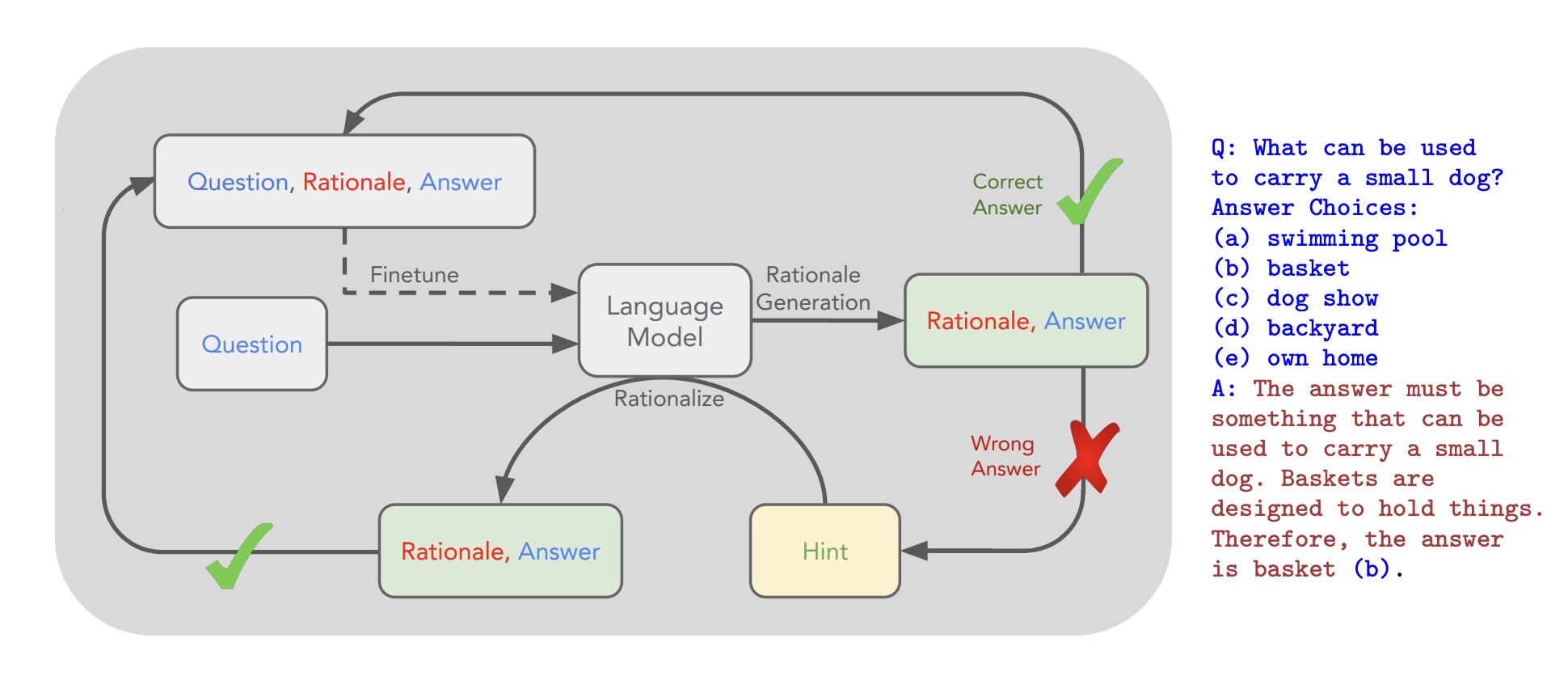

Figure 1: An overview of STaR and a STaR-generated rationale on CommonsenseQA. We indicate the fine-tuning outer loop with a dashed line. The questions and ground truth answers are expected to be present in the dataset, while the rationales are generated using STaR.

图1描述了StaR和StaR生成器在常识QA上的应用。我们用虚线表示微调外循环,问题和真实答案存在于数据集中,而推理则是是使用STaR生成的。

In this paper, we adopt a different approach: by leveraging the LLM’s pre-existing reasoning ability, we iteratively bootstrap the ability to generate high-quality rationales. Specifically, we few-shot prompt a large language model to self-generate rationales and refine the model’s ability further by fine-tuning on those rationales that lead to correct answers. We repeat this procedure, using the improved model to generate the next training set each time. This is a synergistic process, where improvements in rationale generation improve the training data, and improvements in training data further improve rationale generation.

在本文中,我们采用了一种不同的方法:通过利用LLM的现有推理能力,我们迭代地引导生成高质量的推理。具体而言,我们使用少量样例来提示大型语言模型自动生成推理,并通过微调那些导致正确答案的解释进一步改善模型的能力。我们重复这个过程,每次使用改进后的模型生成下一个训练集。这是一个协同作用过程,在此过程中,推理生成方面的改进会提高训练数据质量,并且在训练数据方面取得进展也会进一步提高推理生成能力。

However, we find this loop eventually fails to solve any new problems in the training set because it receives no direct training signal for problems it fails to solve. To overcome this issue, we propose rationalization: for each problem that the model fails to answer correctly, we generate a new rationale by providing the model with the correct answer. This lets the model reason backward—given the correct answer, the model can more easily generate a useful rationale. These rationales are then collected as part of the training data, which often improves overall accuracy.

不幸的是,我们发现,这种循环训练并不能解决任何新的问题,因为它没有直接的训练信号来指导它无法解决的问题。为了解决这个问题,我们提出了“推理化”:对于模型无法正确回答的每个问题,我们通过提供正确答案来生成一个新的推理。这使得模型可以反向推理——给定正确答案,模型可以更容易地生成有用的推理。这些推理被收集为训练数据的一部分,这通常会提高整体准确性。

We thus develop the Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR, Fig. 1) method, a scalable bootstrapping method allowing models to learn to generate their own rationales, while also learning to solve increasingly difficult problems. In our method, we repeat the following process: in each iteration, first construct a finetuning dataset by attempting to solve the dataset using the current model’s rationale generation ability; then, augment this dataset using rationalization, justifying ground-truth answers to problems the model failed to solve; finally, finetune the large language model on the combined dataset.

我们随后开发了自学习推理器(STaR,图1)方法,这是一种可扩展的引导方法,允许模型学习自己的推理,同时也学习解决越来越困难的问题。在我们的方法中,我们重复以下过程:在每次迭代中,首先通过使用当前模型的推理生成能力来尝试解决数据集来构建微调数据集;然后,使用推理化来增强这个数据集,为模型无法解决的问题提供正确答案;最后,在组合数据集上微调大型语言模型。

Applying STaR on arithmetic, math word problems, and commonsense reasoning, we observe it is able to effectively translate a small number of few-shot prompts into a large rationale dataset, yielding dramatic performance improvements. On CommonsenseQA [10], we find STaR improves over both a few-shot baseline (+35.9%) and a baseline fine-tuned to directly predict answers (+12.5%) , and performs comparably to a fine-tuned model that is 30× larger (72.5% vs. 73.0%).

使用STaR进行算术,数学词汇问题和常识推理,我们发现它能够有效地将少量的少量提示转换为大量的推理数据集,从而产生显着的性能提升。在常识QA[10]上,我们发现STaR优于少量的基线(+35.9%)和微调到直接预测答案的基线(+12.5%),并且与30×大的微调模型性能相当(72.5%与73.0%)。

Thus, we make the following contributions:

- We propose a bootstrapping mechanism to iteratively generate a rationale dataset from a few initial examples with rationales—without needing to check new rationales’ correctness.

- We complement rationale generation with rationalization, where a model is tasked with justifying an answer and then fine-tuned as if it had come up with the rationale without any hint. We show rationalization accelerates and improves the bootstrapping process.

- We evaluate these techniques with a variety of ablations in both mathematical and commonsense reasoning domains.

- We propose what is, to our knowledge, the first technique to allow a pre-trained large language model to iteratively use its language modeling capacity to improve itself.

因此,我们做出了以下贡献: - 我们提出了一种引导机制,可以迭代地从少量初始示例和推理中生成推理数据集——而不需要检查新的推理的正确性。

- 我们将推理生成与推理化相结合,其中模型被要求解释答案,然后微调,就像它没有任何提示就想出了推理一样。我们发现推理化能力加速并改善了引导过程。

- 我们在数学和常识推理领域中对这些技术进行了各种各样的消融实验。

- 我们提出了一种技术,据我们所知,这是第一种允许预先训练的大型语言模型迭代使用其语言建模能力来改进自身的技术。

Background and Related Work

In-context Learning Recently, a collection of works has emerged exploring the capacity for large language models to perform in-context learning [11, 12]. In essence, in-context learning treats few-shot learning as a language modeling problem, by showing a few examples in the context (i.e. prompt), and allowing the model to learn and identify the pattern to apply to new examples. Some have studied in-context learning based on the language modeling objective in terms of Bayesian inference [13] while others have attempted to describe the process more mechanistically in terms of “induction heads” [14]. Moreover, differences in prompt configurations have been known to have dramatic effects on few-shot performance. Some have even found that replacing few-shot prompts with a “soft prompt” which can be optimized in embedding space results in noticeable gains [15]. Instead of emphasizing the representation of the question, we focus on the model output; in particular,we focus on the model’s ability to reason through a problem before coming to a conclusion

近年来,一系列的工作已经出现,探索大型语言模型进行上下文学习的能力[11,12]。本质上,上下文学习将少量学习视为语言建模问题,通过在上下文(即提示)中显示几个示例,并允许模型学习并识别应用于新示例的模式。一些人已经研究了基于贝叶斯推理的语言建模目标的上下文学习,而其他人则试图以“归纳头”为基础来更机械地描述这一过程[14]。此外,提示配置的差异会对少量性能产生显着影响。有些人甚至发现,用“软提示”替换少量提示,该提示可以在嵌入空间中进行优化,会产生可观的收益[15]。我们不强调问题的表示,而是关注模型输出;特别是,我们关注模型在得出结论之前对问题进行推理的能力.

Rationales One of the initial works on the impact of rationales on language model performance was [3], showing that training a language model on a dataset with explicit rationales preceding the answer could improve a model’s ability to generate the final answer. However, this required many thousands of training examples to be manually annotated with human reasoning. Recently, [5] demonstrated that step-by-step “scratchpads” can improve fine-tuned LLM performance and generalization on tasks such as arithmetic, polynomial evaluation, and program evaluation. Similarly, [6] used a single

few-shot “chain-of-thought” reasoning prompt in order to improve model performance on a collection of tasks, without fine-tuning. Finally, [16] showed that a curriculum learning approach could help solve formal math problems, as long as 1) they were translated into Lean (a theorem-proving language [17]), 2) one could directly evaluate the validity of the proofs, 3) one could sample numerous potential solutions for each problem, 4) had trained a separate value function model, and 5) started with GPT-f (a model already fine-tuned on a large math dataset [18]). We note that there are many domains where these conditions do not all apply. In addition, works have aimed to explain why rationales have this beneficial effect: some have analyzed their impact from the perspective of latent variable models [19] while others have provided formal proofs of the benefit of intermediate task supervision [20].

关于语言模型性能影响的初步工作之一是[3],显示在答案前面明确的理由的数据集上训练语言模型可以提高模型生成最终答案的能力。但是,这需要人工注释数千个训练示例。最近,[5]证明了逐步“草稿纸”可以提高微调LLM性能和广义化能力,例如算术,多项式评估和程序评估。类似地,[6]使用单个少量的“思维链”推理提示,以提高模型在一系列任务上的性能,而无需微调。最后,[16]显示了一种课程学习方法可以帮助解决正式的数学问题,只要1)它们被翻译成Lean(一个定理证明语言[17]),2)可以直接评估证明的有效性,3)可以为每个问题采样许多潜在的解决方案,4)已经训练了一个单独的价值函数模型,5)从GPT-f(已经在大型数学数据集上微调的模型[18])开始。我们注意到,在许多领域,这些条件并不适用。此外,有些工作旨在解释为什么理由有这种有益的效果:一些人从潜在变量模型的角度分析了它们的影响[19],而其他人提供了中间任务监督的好处的正式证明[20]。

Iterated Learning A variety of iterated learning algorithms have been proposed, where solutions or successful methods which are found are in turn used to find additional solutions [21, 22, 16]. [21] introduced Expert Iteration (ExIt), a reinforcement learning technique serving as an inspiration for our approach. Essentially, it consists of a loop of self-play by an “apprentice,” followed by imitation learning with feedback from a slower “expert” and then the replacement of the expert with the nowimproved apprentice. [16] builds off of ExIt for formal reasoning, while [22] applies iterated learning to visual question answering using modular networks which can be combined compositionally. There are further similarities between STaR and expert iteration methods [21]. For example, filtering generated examples based on whether their ultimate answer matches the target can be seen as expert feedback. However, we have a fixed “expert” and do not train a separate value function.

我们提出了各种迭代学习算法,其中找到的解决方案或成功的方法又被用来找到其他解决方案[21,22,16]。[21]引入了专家迭代(ExIt),这是我们方法的灵感来源。本质上,它由一个“学徒”的自我游戏循环组成,然后是由一个较慢的“专家”提供反馈的模仿学习,然后用现在改进的学徒替换专家。[16]为正式推理建立了ExIt,而[22]将迭代学习应用于使用可以组合成分的模块化网络的视觉问题回答。STaR和专家迭代方法之间有进一步的相似之处[21]。例如,根据最终答案是否与目标匹配来过滤生成的示例可以看作是专家反馈。但是,我们有一个固定的“专家”,并且不训练单独的价值函数。

Natural Language Explanations Natural language explanations have also been discussed from the perspective of explainable machine learning, focusing on justification rather than reasoning [23, 24]. The motivation for this line of work is largely grounded in explainable decision making, and similarly to [3], generally does not find that requiring post-hoc explanations improves model performance.

自然语言解释也已从可解释的机器学习的角度讨论,重点是正当性而不是推理[23,24]。这一工作的动机主要是基于可解释的决策,类似于[3],通常不会发现要求事后推理会提高模型性能。

Method

Rationale Generation Bootstrapping (STaR Without Rationalization)

We are given a pretrained LLM M and an initial dataset of problems x with answers y: . Our technique starts with a small prompt set P of examples with intermediate rationales r: , where P << D (e.g. P = 10). Like standard few-shot prompting, we concatenate this prompt set to each example in D, i.e. , which encourages the model to produce a rationale rˆi for xi followed by an answer yˆi . We assume that rationales that lead to correct answers are of better quality than those that lead to incorrect answers. Therefore, we filter the generated rationales to include only the ones which result in the correct answer (yˆi = yi). We fine-tune the base model M on this filtered dataset, and then restart this process by generating the new rationales with the newly fine-tuned model. We keep repeating this process until the performance plateaus. Note that during this process, once we collect a new dataset, we train from the original pre-trained model M instead of continually training one model to avoid overfitting. We provide an outline of this algorithm in Algorithm 1.

我们被给了一个预训练的LLM M和一个初始的问题数据集x和答案y:。我们的技术从一个小的提示集P开始,P是带有中间理由r的示例:,其中P << D(例如P = 10)。像标准的少量提示一样,我们将这个提示集连接到D中的每个示例中,即,这鼓励模型产生一个理由rˆi为xi后跟一个答案yˆi。我们假设导致正确答案的理由比导致错误答案的理由更好。因此,我们过滤生成的理由,只包括导致正确答案的理由(yˆi = yi)。我们在这个过滤的数据集上微调基本模型M,然后通过使用新微调的模型生成新的理由来重新启动这个过程。我们一直重复这个过程,直到性能达到平台。请注意,在这个过程中,一旦我们收集了一个新的数据集,我们就从原始预训练模型M开始训练,而不是不断训练一个模型以避免过度拟合。我们在算法1中提供了这个算法的概述。

STaR can be seen as an approximation to an RL-style policy gradient objective. To see this, note that M can be viewed as a discrete latent variable model ; in other words, M first samples a latent rationale r before predicting y. Now, given the indicator reward function 1(ˆy = y), the total expected reward across the dataset is

STaR可以看作是RL风格策略梯度目标的近似。要看到这一点,请注意,M可以被看作是一个离散的潜在变量模型;换句话说,M首先对预测y采样一个潜在的理由r。现在,给定指示奖励函数1(ˆy = y),数据集的总期望奖励是: